Microservices Architecture Deep Dive Part Six: Distributed Transactions

Part 1 - Microservices Architecture Deep Dive

Part 2 - API Gateways and Backend For Frontend Pattern

Part 3 - Microservices Communication

Part 4 - Service Discovery

Part 5 - Service Mesh

Part 6 - Distributed Transactions you are here

What Is A Transaction?

A database transaction symbolizes a unit of work, performed within a database management system (or similar system) against a database, that is treated in a coherent and reliable way independent of other transactions. A transaction generally represents any change in a database.

In a database management system, a transaction is a single unit of logic or work, sometimes made up of multiple operations. Any logical calculation done in a consistent mode in a database is known as a transaction. One example is a transfer from one bank account to another: the complete transaction requires subtracting the amount to be transferred from one account and adding that same amount to the other.

A database transaction, by definition, must be atomic (it must either be complete in its entirety or have no effect whatsoever), consistent (it must conform to existing constraints in the database), isolated (it must not affect other transactions) and durable (it must get written to persistent storage).Database practitioners often refer to these properties of database transactions using the acronym ACID.

The Problem

In a monolithic architecture getting the transaction ACID properties right was already very difficult. People from the past and the present have worked tirelessly to make the database transactions ACID. But now we have an entirely different problem regarding database transactions.

Now we have a distributed microservices architecture in which every service has its own database, but for the end user all these microservices combine and make up a single service and the end user can not tell the difference. Thats the end goal of distributed systems.

But Now what previously needed to be ACID transaction on a single database has to be ACID over multiple microservices databases.

Distributed Transaction

A distributed transaction operates within a distributed environment, typically involving multiple nodes across a network depending on the location of the data. A key aspect of distributed transactions is atomicity, which ensures that the transaction is completed in its entirety or not executed at all. It’s essential to note that distributed transactions are not limited to databases.

Databases are common transactional resources and, often, transactions span a couple of such databases. In this case, a distributed transaction can be seen as a database transaction that must be synchronized (or provide ACID properties) among multiple participating databases which are distributed among different physical locations. The isolation property (the I of ACID) poses a special challenge for multi database transactions, since the (global) serializability property could be violated, even if each database provides it.

The Consistency Challenges

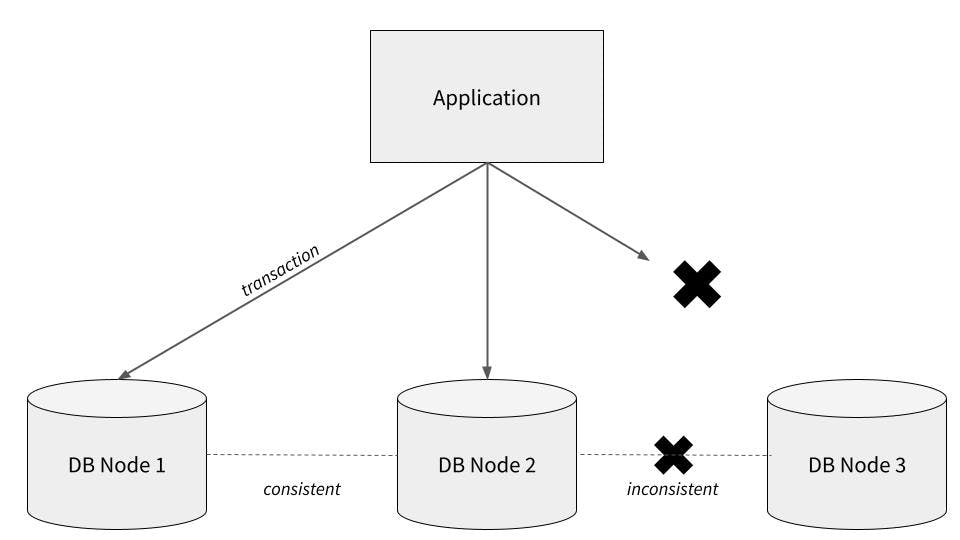

Distributed transactions are more complex than transactions on a single-instance database because we need some way to ensure that each database node is consistent with the others.

The diagram below illustrates one potential problem with distributed transactions. Imagine we have an application attempting to commit a transaction to three separate database nodes (perhaps the same data is replicated on all three nodes, or perhaps the transaction affects multiple rows, and the different rows are stored on different nodes). In the diagram, the transaction is successfully written to the first two nodes, but fails to write to the third — perhaps due to a network disconnection or an error on the node itself. This introduces a state of inconsistency — the first two nodes and the third node “disagree” about what data is correct.

Needless to say, inconsistency in a database can cause all kinds of problems, particularly when it comes to the kinds of workloads that use transactions (payment processing systems, for example).

So, how can we ensure our database remains consistent even when it is partitioned across multiple nodes? There are a variety of approaches, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. Let’s take a look at some real-world examples of workable patterns for distributed transactions.

The Solution

In the following paragraphy i will explain the ways in which distributed transaction are done in the wild using an example.

Example System: Travel Booking

Scenario:

A user books a vacation package. The process includes:

- Flight Service: Books a flight.

- Hotel Service: Reserves a hotel room.

- Car Rental Service: Reserves a rental car.

Each service operates independently but must work together to fulfill the booking. A failure in any service should result in a rollback.

Orchestration And Choreography

1. Orchestration

In orchestration there needs to be a coordinator (a central controller ) which manages the entire workflow.

How it works:

The Travel Booking Orchestrator service calls the Flight, Hotel, and Car Rental services in sequence. If a failure occurs (e.g., flight booking fails), the orchestrator initiates compensating actions (e.g., cancel hotel and car reservations).

Flow:

- User sends a booking request to the orchestrator.

- Orchestrator calls the Flight Service.

- If successful, it calls the Hotel Service.

- If successful, it calls the Car Rental Service.

- If any service fails, orchestrator rolls back previous bookings.

Advantages:

- Centralized control simplifies monitoring and debugging.

- Easier to implement retries and compensations.

Disadvantages:

- Orchestrator becomes a single point of failure.

- Tight coupling between orchestrator and services.

2. Choreography

Each service acts independently and reacts to events.

How it works:

- The Flight Service publishes an event (FlightBooked) after successful booking.

- The Hotel Service listens to FlightBooked and books a hotel, then publishes HotelBooked.

- The Car Rental Service listens to HotelBooked and reserves a car.

- If a failure occurs, services handle compensations independently.

Flow:

- User sends a booking request to the Flight Service.

- Flight Service publishes a FlightBooked event.

- Hotel Service subscribes to FlightBooked and publishes HotelBooked after success.

- Car Rental Service subscribes to HotelBooked and proceeds similarly.

Advantages:

- Decentralized, no single point of failure.

- Loose coupling improves service independence.

Disadvantages:

- Complex to manage compensating actions.

- Debugging and monitoring are harder.

Saga Pattern

Saga divides the transaction into a series of steps, each with a compensating action if it fails.

In our example:

- Flight Service books a flight. If it fails, no action is needed (initial step).

- Hotel Service reserves a hotel. If it fails, it cancels the hotel reservation.

- Car Rental Service reserves a car. If it fails, it cancels the car reservation.

- If any service fails, previous steps execute compensating actions in reverse order.

Advantages:

- Scales well with microservices.

- Better performance since each step commits locally.

Disadvantages:

- Complex to design compensating actions.

- No strict consistency; eventual consistency is guaranteed.

The saga pattern could be implemented as a Choreographed as well as Orchestrated process but mostly its always Choreographed.

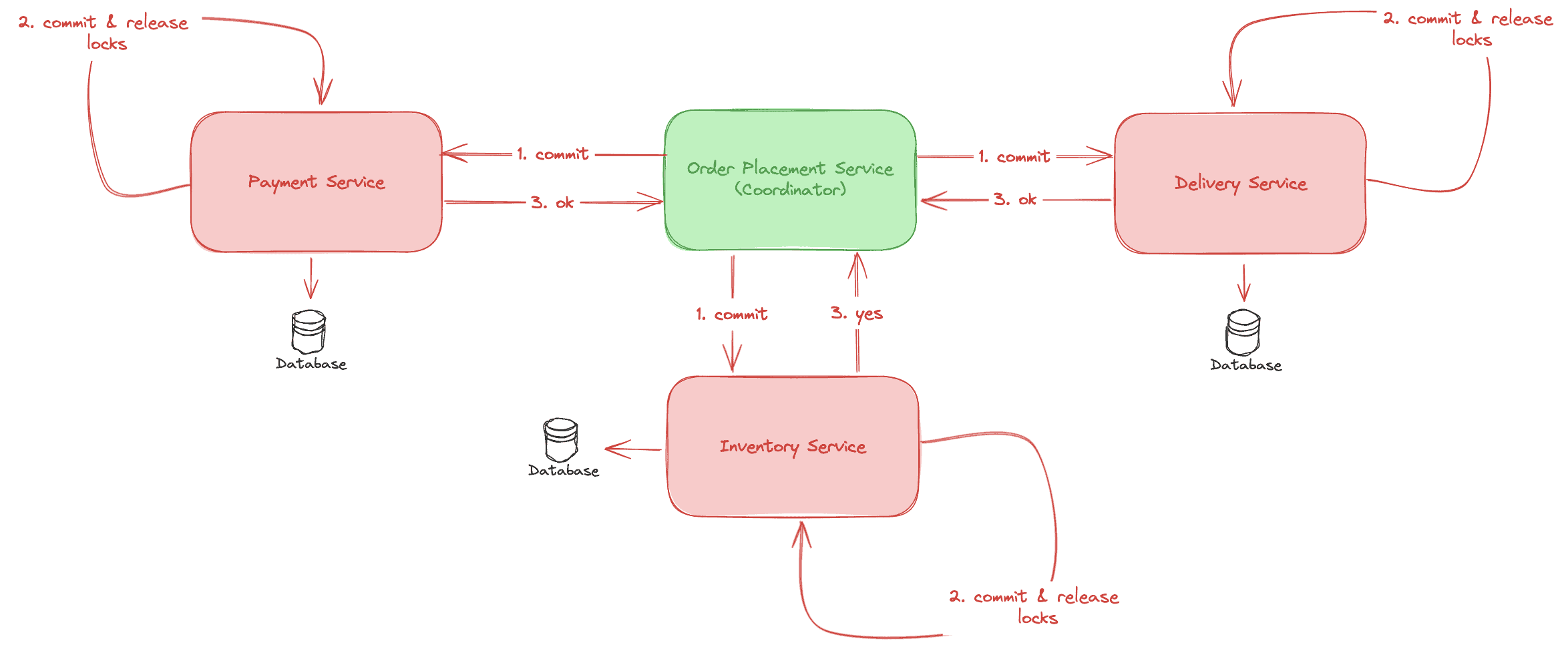

Two Phase Commit

2PC is a protocol to ensure strict consistency across distributed services.

In our example:

Phase 1: Prepare

- Flight, Hotel, and Car Rental services prepare resources and lock them.

- They notify the coordinator (a central transaction manager) of readiness.

Phase 2: Commit or Rollback

- If all services are ready, the coordinator sends a “commit” command.

- If any service fails, the coordinator sends a “rollback” command.

Advantages:

- Ensures strict consistency.

- Ideal for transactional systems requiring ACID compliance.

Disadvantages:

- Poor scalability, locks may reduce performance.

- Single point of failure if the coordinator crashes.

the 2PC is always Orchestrated

Comparison

| Feature | Saga | Two-Phase Commit (2PC) |

|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Eventual consistency | Strict consistency |

| Performance | High | Low (due to locking) |

| Failure Handling | Compensating actions | Rollback entire transaction |

| Complexity | High (due to compensations) | Medium |

| Scalability | Scales well | Limited scalability |

| Best Use Case | Microservices, high scale | ACID transactions |